Adam Silverstein, FleishmanHillard

917-697-9313; Adam.Silverstein@fleishman.com

Stephen Fitzmaurice, ASH

561-506-6890; SFitzmaurice@hematology.org

More options for both curative and supportive therapies for patients as progress continues in under-served disease

(Black PR Wire) San Diego — At the 60th American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition in San Diego, researchers announce findings from four studies that could greatly expand access to both curative and supportive treatments for individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD) worldwide.

The results of two first-in-human trials suggest promising initial results for ground-breaking approaches to stem cell transplantation and gene therapy for SCD. Another, the largest prospective trial of hydroxyurea ever conducted in Africa, suggests that this drug –– long the standard of care for SCD in developed countries ––is safe and effective and can confidently be used in low-resource countries. Additionally, a large-scale study of in-hospital death rates provides reassurance that opioid medications may safely be used to treat acute SCD-related pain in the hospital.

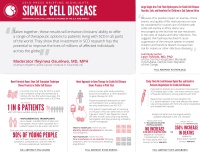

“Taken together, these results will enhance clinicians’ ability to offer a range of therapeutic options to patients living with SCD in all parts of the world,” said press briefing moderator Ifeyinwa Osunkwo, MD, MPH, of Atrium Health’s Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte, NC. “They show that investment in SCD research has the potential to improve the lives of millions of affected individuals across the globe.”

Individuals with SCD, an inherited blood disease, produce abnormal hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that attaches to oxygen in the lungs and carries it to all parts of the body. Red blood cells that contain normal hemoglobin are donut-shaped and flexible so that they can travel smoothly through the smallest blood vessels. In SCD, however, the red blood cells are sickle-shaped and rigid and can get stuck in these vessels, blocking the flow of blood and oxygen to the body and leading to intense pain and other serious issues such as stroke, infection, pulmonary complications, and even death.

Supporting SCD research and access to care is a chief priority for ASH, which in 2016 launched a multifaceted initiative to address the burden of this disease both in the United States and globally.

“ASH is committed to accelerating the development of new therapies for this community, which currently has had very few treatment modalities and even fewer curative options,” said Dr. Osunkwo. “The results being presented today demonstrate that we are indeed on the brink of a new era in SCD research and treatment.”

This press conference will take place on Saturday, December 1, at 7:30 a.m. PST in Room 22, San Diego Convention Center.

Novel Parental-Donor Stem Cell Transplant Technique Shows Promise in Sickle Cell Disease

Significantly Improved Long Term Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL) and Neurocognition Following Familial Haploidentical Stem Cell Transplantation (HISCT) Utilizing CD34 Enrichment and Mononuclear (CD3) Addback in High Risk Patients with Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) [162]

In a new study, ninety percent of young people with SCD who received blood-forming stem cells from a parent were alive and healthy one year later, free of symptoms and complications. They did not need to take immune-suppressive medications, and in some instances their cognitive processing speed — that is, how quickly they were able to learn, think, and communicate — in some instances improved.

With a median follow-up of over three years, there have been no recurrences of sickle cell pain crises, no patients have required blood transfusions, and no new patients have developed graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a complication in which transplanted cells attack healthy tissues and organs, said lead study author Mitchell Cairo, MD, of New York Medical College in Valhalla, NY.

“These individuals have a completely new lease on life,” Dr. Cairo said. “They’re either stable or better in every organ system. What’s more, this could mean that every person with SCD who has a living parent could have a potential donor in their family.”

Currently, the only cure for SCD is a stem cell transplant using cells donated by a brother or sister who has the same tissue type, has the same mother and father, and is SCD-free. According to Cairo, only about one in six patients with SCD has a suitable sibling donor.

This study focused on a newer, modified form of stem cell transplant in which the donor’s bone marrow needs to be only 50 percent the same as the recipient’s. In this type of transplant, known as a haploidentical transplant, the patient’s mother or father can be the stem cell donor. In previous studies of haploidentical transplants for SCD, however, the rate of transplant failure has been high.

Cairo and his team sought to reduce both the rate of transplant failure and the risk of serious post-transplant complications by enriching stem cells with a type of protein called CD34 that is understood to be important in promoting the acceptance of transplanted blood-forming cells. In addition, they added back the patients’ T cells (after the transplant). T cells are a type of immune cell that has also been shown to promote the acceptance of transplanted blood-forming cells while not increasing rates of GVHD.

In this study, 19 patients age 3-20 with frequent or severe SCD symptoms received transplanted stem cells; 15 patients received cells from their mothers, and four from their fathers.

Engraftment, wherein the transplant recipient’s body accepts the new stem cells and the stem cells begin to produce new blood and immune cells, is one of the first steps in a successful stem cell transplant, and it occurred in all 19 patients in the study.

Chimerism is a measure of the durability of engraftment. Full donor chimerism means that 100 percent of the cells in the patient’s bone marrow and blood have developed from the donor’s stem cells. Mixed chimerism means that some of the transplant recipient’s own cells are also present in the bone marrow and blood. At one year following the transplant, the rate of chimerism was 97 percent. One patient developed acute GVHD within 100 days of the transplant and another developed chronic GVHD more than 100 days after the transplant.

Follow-up tests performed two years after the transplant showed that patients had stable or improved heart and lung function. Imaging tests showed no evidence of strokes or inflammation of blood vessels in the brain, two potentially serious complications of SCD. Tests of memory, language, intellectual functioning, and ability to plan, focus on tasks, and manage emotions all showed stability or improvement.

These results suggest that nearly 90 percent of patients (17 of 19) with SCD will go on to lead normal lives after undergoing a stem cell transplant that incorporates the techniques researchers used in this study, Dr. Cairo said. He cautioned, however, that the procedure is not successful in all patients, adding that whether patients will develop late adverse effects is not yet known. Dr. Cairo and his team have received funding to continue to follow this group of patients for another three years to assess the risk of long-term complications.

This study was supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Mitchell Cairo, MD, New York Medical College, will present this study during an oral presentation session on Saturday, December 1, at 12:00 noon PST, Room 24B, San Diego Convention Center.

Novel Approach to Gene Therapy for SCD Shows Promise in Pilot Trial

Flipping the Switch: Initial Results of Genetic Targeting of the Fetal to Adult Globin Switch in Sickle Cell Patients [1023]

One adult patient with SCD is doing well after receiving an infusion of his own stem cells in which a genetic “switch” was flipped on to induce the cells to both start producing healthy hemoglobin and stop producing unhealthy (sticky or harmful) “sickle” hemoglobin, according to a new study. This first-in-human pilot study provides a proof of principle for this novel approach to gene therapy for SCD, said lead study author Erica B. Esrick, MD, hematologist at Dana-Farber /Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.

“This is the first gene therapy trial in any disease –– not just in SCD –– to use this novel engineering strategy,” Dr. Esrick said. “Although only one patient has so far completed treatment, the results we’re seeing are very encouraging and support the promising preclinical data that were the basis for this trial.”

Currently, the only established cure for SCD is a transplant of healthy stem cells from a matched sibling donor. However, many patients with SCD do not have a suitable sibling donor and sometimes stem cell transplants may fail. Gene therapy is an alternative approach that uses the patient’s own stem cells and does not rely on the availability of a compatible donor.

This novel technique for gene therapy for SCD is inspired by changes observed in hemoglobin before and after birth. Fetuses in the womb need to extract oxygen from their mother’s circulation. For this purpose, they have a special type of hemoglobin known as fetal hemoglobin that accepts and releases oxygen at lower blood and tissue oxygen levels compared with adult hemoglobin. Soon after birth, a switch is turned off and fetal hemoglobin begins to be replaced by adult hemoglobin –– or, in infants with SCD, with sickle hemoglobin.

Researchers have long recognized that fetal hemoglobin inhibits the development of sickle hemoglobin polymers, the basis of sickled cells, from forming. More recently, preclinical research from Boston Children’s Hospital has shown that suppressing the action of a protein known as BCL11A can reverse SCD by reactivating fetal hemoglobin production.

In the current study, David Williams, MD, chief scientific officer at Boston Children’s Hospital, and colleagues devised a technique to genetically engineer an inactivated virus to deliver a gene that blocks the action of BCL11A in red blood cells using the cell’s own machinery called a microRNA. The key feature of the new approach is targeting BCL11A with a structure they named a shMIR.

“We are in effect providing the cells with instructions to stop producing sickle hemoglobin and start producing fetal hemoglobin instead,” Dr. Esrick said.

To date, four adult patients have been enrolled in the trial, with one having received this gene therapy. This patient, who, prior to transplant, required monthly blood transfusions to alleviate SCD symptoms, has required only a single transfusion in the six months following treatment, with no transfusions required following engraftment. Blood tests show high levels of fetal hemoglobin in this patient.

“He has had no pain or other symptoms that could be attributed to SCD,” Dr. Esrick said. “He’s back to his normal life.”

Two other patients are awaiting transplant, with the fourth patient set for stem cell collection by year-end.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Erica B. Esrick, MD, Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, will present this study during an oral presentation session on Monday, December 3, at 6:15 p.m. PST, Room 6B, San Diego Convention Center.

Large Single-Arm Trial Finds Hydroxyurea for SCD Feasible, Safe, and Beneficial for Children in Sub-Saharan Africa

Realizing Effectiveness Across Continents with Hydroxyurea (REACH): A Prospective Multi-National Trial of Hydroxyurea for Sickle Cell Anemia in Sub-Saharan Africa [3]

The largest prospective trial of hydroxyurea for sickle cell anemia (SCA)as shown that this drug — long the standard of care for treating SCA in developed countries — is feasible, accepted, well tolerated, and safe for children living in sub-Saharan Africa. Researchers report that there are distinct clinical benefits for children receiving hydroxyurea.

After a median of 2.5 years of treatment, children in the trial experienced less pain and anemia, fewer episodes of malaria and other infections, and lower rates of transfusions and death compared with rates during the pre-treatment screening phase of the trial.

“Because of its positive impact on anemia, clinical events, and quality of life, hydroxyurea can now be considered for routine care of children with sickle cell anemia in Africa,” said lead study author Leon Tshilolo, MD, PhD, of the Centre Hospitalier Monkole in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Though some previous studies had suggested that hydroxyurea treatment might put children at higher risk for malaria by suppressing the immune system, which defends the body against infections, this study found that not to be the case.

“We’re very encouraged by the fact that we saw reductions in the rates of malaria and other infections,” said Dr. Tshilolo. “This suggests that hydroxyurea doesn’t cause suppression of the immune system in treated children and therefore doesn’t increase their risk for malaria or other infectious diseases.”

Ample data support the value of hydroxyurea treatment for children with SCA who live in high-resource countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and European countries, Dr. Tshilolo said. However, prior to this study, data were lacking on the drug’s benefits for children living in sub-Saharan Africa, where the burden of SCA is highest and rates of malaria and other infectious diseases, as well as undernutrition and poverty, are extremely high.

A total of 635 children ages between 1-10 from four African countries — Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, and Uganda — were enrolled in the trial. Four children died during a two-month screening period before treatment began; 25 other children withdrew from the trial for other reasons during the screening period.

The remaining 606 children began six months of treatment with a modest dose of hydroxyurea. After six months, if no adverse effects were observed, the dose was gradually increased, based on weight and other criteria, to a maximum tolerated dose (MTD), or the highest dose that could be given without adverse effects being seen.

Five percent of treated patients dropped out of the trial or died. Ninety-seven percent of the remaining completed all scheduled study visits and 94 percent completed all the required laboratory tests. rate of toxicities was similar between the screening period and the treatment phase. Patients received the hydroxyurea capsules, all lab tests, and transportation to clinic visits at no charge, which may have contributed to the high rates of retention and adherence to treatment. The close monitoring for adverse effects that children received throughout the trial may also have contributed to the benefits of treatment observed in the study, Dr. Tshilolo said.

Dr. Tshilolo and his colleagues plan to continue to follow the children in this study for several years to observe the effects of hydroxyurea treatment on their growth and sexual development, as well as on the function of organs such as the brain, liver, spleen, and kidneys, and the children’s intellectual performance as they get older.

The costs of hydroxyurea treatment and associated laboratory monitoring will be a major factor limiting more widespread use of the drug to treat SCA in Africa. “The current cost of treatment is beyond the daily wage of most families living in sub-Saharan Africa,” Dr. Tshilolo said. “We hope that treatment will be made available to more patients through outside financial support, as is the case with treatment for HIV infection in several African countries.”

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (a component of the National Institutes of Health) and the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. Bristol-Myers Squibb donated the hydroxyurea capsules.

Leon Tshilolo, MD, PhD, Centre Hospitalier Monkole, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, will present this study during the Plenary Scientific Session on Sunday, December 2 at 2:00 p.m. PST, Hall AB, San Diego Convention Center.

Study Finds No Link Between Opioid Use and Death in Patients Hospitalized for Sickle Cell Disease

Opioid Use Is Not Associated with in-Hospital Mortality Among Patients with Sickle Cell Disease in the United States: Findings from the National Inpatient Sample [315]

Attacks of excruciating pain are the most common cause of hospital admission among patients with SCD, and opioid medications are a mainstay of treatment for these attacks, known as pain crises. Researchers at Boston University School of Medicine wanted to know whether the U.S. opioid epidemic, which has resulted in a marked increase in opioid-related overdoses and deaths over the past two decades, may have affected the death rate among people with SCD who were treated with opioids in the hospital to relieve these pain crises.

A new study analyzing data from a large database on hospital inpatients appears to show that the use of opioid medications for pain control in patients with SCD is relatively safe, said lead investigator Oladimeji A. Akinboro, MBBS, of the Boston University School of Medicine.

In-hospital death rates among those with SCD did not increase over a 15-year period despite an increase in hospitalization rates for most adults with SCD over the same period, Dr. Akinboro said.

“We do not see a relationship between opioid use and death in patients who are hospitalized for SCD,” he said, adding that the overwhelming majority of patients with SCD need strong pain medication to control acute pain during crises.

“Adults with SCD are hospitalized frequently,” he added. “We expected that if opioid-related mortality had increased in this population, the increase would be apparent in hospital inpatient mortality data. It is reassuring to find that opioid use during acute pain crisis does not seem to have led to higher mortality in this population.”

The hallmark of SCD is stiff, sickle-shaped red blood cells that don’t flow smoothly through the blood vessels as normal red blood cells do. A pain crisis occurs when these sickle-shaped red blood cells get stuck in blood vessels, slowing or blocking blood flow and preventing oxygen from reaching all parts of the body.

Dr. Akinboro and his colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample, the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient health care database in the United States, which contains data from more than 7 million hospital stays each year. They identified more than 1.7 million hospitalizations for patients with SCD between 1998-2013. They examined rates of hospitalization and in-hospital death both for this entire patient population and for specific age groups (0-17 years, 18-44 years, 45-64 years, and 65 years and over) and by the region of the country where patients were hospitalized (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West).

The analysis found no significant increase in the rate of in-hospital death among those with SCD over the 15-year period examined. By contrast, the death rate related to prescription opioids among the U.S. population without SCD increased 350 percent between 1999-2013.

Overall, the hospitalization rate for patients with SCD declined from 39 per 100,000 people in 1998 to 27 per 100,000 in 2002 and did not change significantly from 2002-2013. Among adults in the 18–44 age group, however, the hospitalization rate increased significantly, from 43 per 100,000 in 2002 to 71 per 100,000 in 2013. For adults ages 65 and over, the hospitalization rate also increased significantly, from 2.7 per 100,000 in 1998 to 5.4 per 100,000 in 2013.

According to subgroup analysis, the rates of opioid-related hospitalizations relative to the total number of hospitalizations in the sickle cell population were stable over time and similar to the relative rates in the general population. However, unlike in the general population in which inpatient deaths from opioid-related admissions increased over time, inpatient deaths related to opioid toxicity and/or overdose were almost non-existent over the entire study period. This further reinforces the study conclusions that opioid use for pain control should be considered safe in the sickle cell disease population, according to Dr. Akinboro.

Dr. Akinboro said further research is needed to clarify the reasons why hospitalization rates climbed in these two age groups, but he suspects one reason may be lack of coordination of medical care for adults with SCD. Another possible explanation is that people with SCD are now living longer than they did in the past and are developing other health problems as they age, he said.

“One important message from this study is that health care providers need to keep tabs on their patients with SCD and make sure that their care is coordinated,” he said.

Oladimeji A. Akinboro, MBBS, Boston University School of Medicine, will present this study during an oral presentation session on Sunday, December 2, at 7:30 a.m. PST, Room 28D, San Diego Convention Center.

The study authors and press program moderator will be available for interviews after the press conference or by telephone. Additional press briefings will take place throughout the meeting on large-scale practice-changing clinical trials, lasting results in CAR T-cell therapies, and looking to the future in the era of personalized medicine. For the complete annual meeting program and abstracts, visit http://www.hematology.org/annual-meeting. Follow @ASH_hematology and #ASH18 on Twitter and Instagram, and like ASH on Facebook for the most up-to-date information about the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) (www.hematology.org) is the world's largest professional society of hematologists dedicated to furthering the understanding, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disorders affecting the blood. For 60 years, the Society has led the development of hematology as a discipline by promoting research, patient care, education, training, and advocacy in hematology. The Society publishes Blood (www.bloodjournal.org), the most cited peer-reviewed publication in the field, as well as the newly launched, online, open-access journal, Blood Advances.